In the 1968 Olympics, a guy named Dick Fosbury used a technique the world hadn’t seen at that level before.

He ran at an angle, turned midair, and flung himself backward and headfirst over the bar.

Fosbury had been refining this technique for years, but this was the first time the so-called Fosbury Flop appeared on the Olympic stage.

Before him, most high jumpers used the straddle technique—approaching face-on, leading with one leg while keeping the hips and trailing leg beneath them.

So when Dick did what looked like an airborne backbend thrust /dolphin out of water, people were… confused.

His technique was so strange that some thought he was mocking the sport.

Even his own coach discouraged him from using it in competition. It didn’t look right. It wasn’t how high jumpers were “supposed” to jump.

But the rules didn’t say how you had to get over the bar—just that you had to clear it. And the higher you cleared it, the better.

Here’s how Fosbury’s method was biomechanically brilliant:

He let his center of mass pass under the bar while his body sailed over it.

The others had to get their entire center of mass over the bar, which meant working harder to achieve the same outcome.

Dick’s technique worked so well that he won gold and set a new Olympic record.

The Fosbury Flop became the dominant technique within a few years, and remains a masterclass in how applying physics more effectively can change the game.

why am I bringing up revolutionary high jump techniques on a blog about pole dance?

Yes, he too was making moves over a pole. But that’s not why.

Its because sometimes… I teach things that make people tilt their heads and go:

“Wait—are we allowed to do that? that’s not how we’ve been taught to do it.”

I love movement history. But I’m not here to stick with tradition when tradition fails to be adaptable or accessible.

Instead of clinging to how it’s always been done, I ask:

What if it didn’t have to be so effortful?

What if there’s a way that makes more structural sense?

What promotes more flow, and actual success?

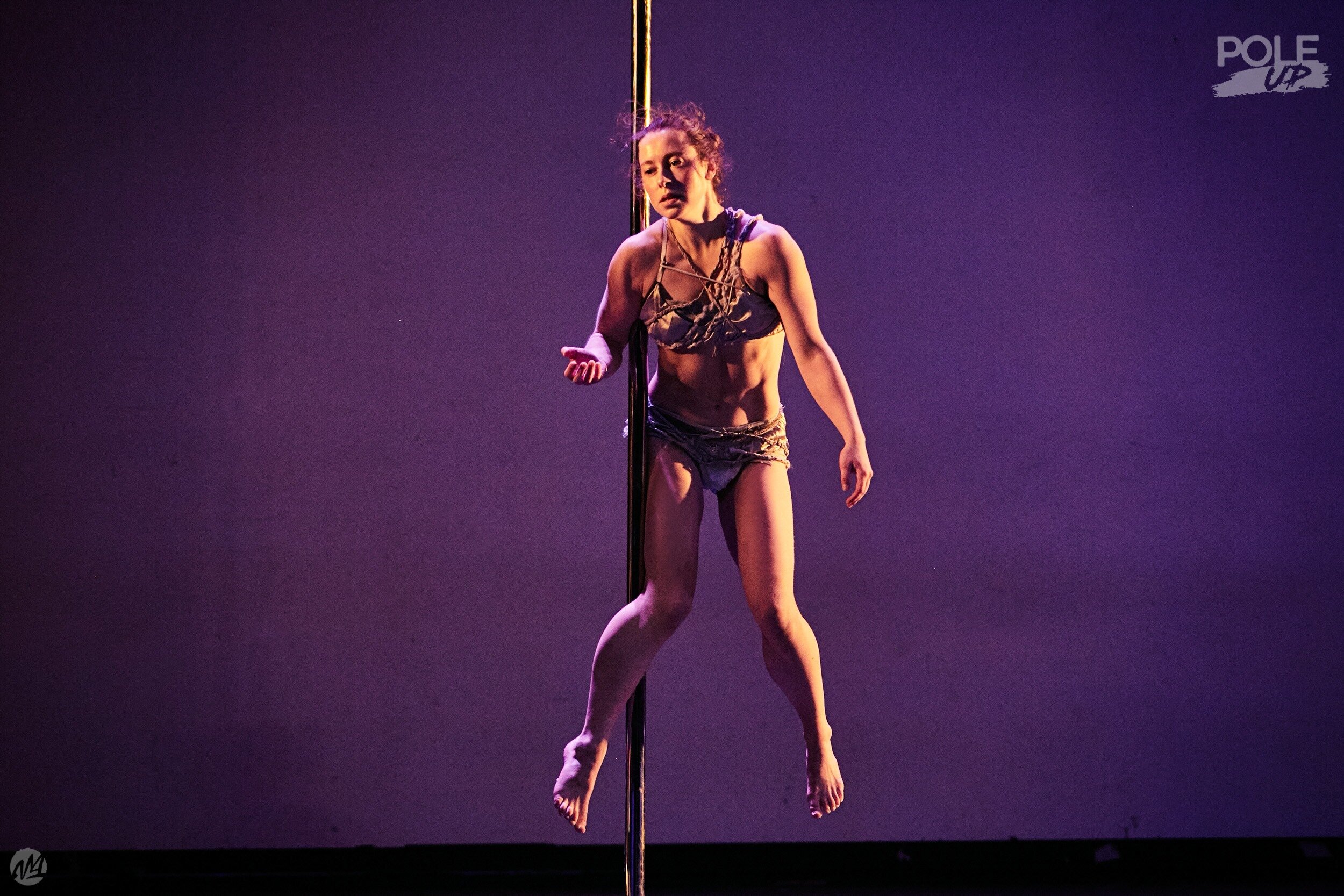

These questions led me to an approach to inverts that doesn’t always look conventional—but consistently helps people of diverse body types actually get upside down.

As the arms raise, the CM/COM shifts. Postural changes on the pole can also shift your weight away from your pelvis, making your lower half “lighter”.

One of the first things I help students understand is that the location of their Center of Mass (COM) relative to the pole really matters.

We all have a center of mass. If we all stand in the same position, it will be located in slightly different places due to our structure.

Even subtle position changes change our COM.

When you want something to be easier / less heavy, you want to explore shifting your COM.

Traditionally, people hold the pole in their armpit and “crunch” their way up into an invert.

For many, this COM far from the pole, heavy-by-default approach is simply too hard.

It leaves many pole dancers stuck in rounded, turtle-like shape, with hips that never quite make it up or upper back strain from the position and effort.

There are simple things we can do to make the experience of the bottom half feel lighter—like making the top half longer, and moving the pole closer to the COM.

…like the #pdwaistholdinvert

No, not all inverts will happen this way—just like not all high jumps are Fosbury Flops.

Do I think my method will revolutionize the entire world of Pole Dance?

No.

Will it land me a Netflix biopic?

Also unlikely.

But…

I do believe what I teach in InvertReady is just as counterintuitive to the way people have learned inverts (we even go sideways!)—and just as effective at making things easier—as the Fosbury Flop was to high jump.

The techniques I share consistently knocks others out of the park when it comes to helping people get upside down without hunching or straining.

The progressions I teach were developed in direct response to watching students struggle with cues that made little biomechanical sense.

Once you learn to invert in ways that:

actually help you get your hips up without rounding,

allow for a multitude of smooth transitions, and

meet you right where you are—

…you’ll probably wonder:

“Why the hell didn’t anyone show me this sooner?”

Learning to invert in a way where the technique uses your body weight to assist you, instead of against you?

Call it what you want.

It works.

👉 InvertReady is open for registration now.

Learn more here.